“How are you doing?” someone asks. A friend answers, “Okay. I mean, pandemic okay.”

Pandemic okay is a very specific kind of okay. It means, “Technically things are Fine yet nothing is fine.” Pandemic okay means something different for everyone, especially for people who were in precarious positions before this all happened.

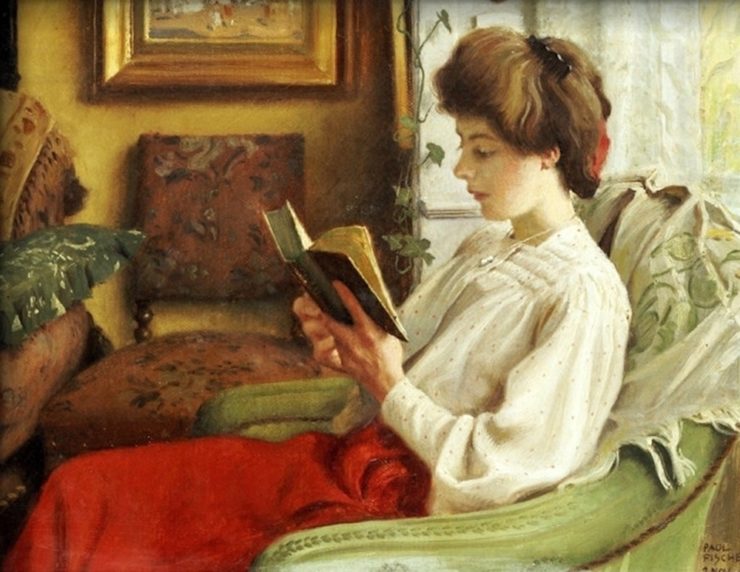

In the face of “pandemic okay,” it’s easy to make some guesses about why I want a certain kind of read right now. How everyone exists within this kind of “okay”—or outside of it—is deeply individual. For me, on a reading level, it’s been a narrative about-face, a shift from the space-stress stories I wanted last year to a desire for stories about interiority, about people being okay with themselves. And these books feel hard to come by.

Here is a short and absolutely incomplete list of things the protagonists of my favorite fantasy books have done:

- Saved the world from the lord of death.

- Saved the world from monsters from beyond.

- Saved the land from a wicked king. (Many wicked kings in many books.)

- Saved the world from an invading host of monsters.

- Saved the world from an invading host from another world.

- Saved as much of the world as possible from total disaster.

- Fulfilled a prophecy and saved the world.

- Defeated a deadly spirit and saved the world.

You get the picture. The world-saving isn’t always specified as the whole world, but existence as the characters know it is threatened in some way, and they either have to or are the only ones who can save it. I love a good save. I love drama and high stakes and the impossible tasks that only a few people could possibly pull off. But right now, I want so little of that.

I have a Helen Oyeyemi quote written on a post-it on the wall by my desk: “I like the entire drama of whether the protagonist is going to be OK inside herself.” This, I thought when I read it. This is what I want to read.

You can have this drama of the self inside a story about saving the world; the books that can manage both are excellent. But lately I want things ticked down a notch, or several notches. Sometimes the world-saving is still there, but it hovers on the periphery, but almost incidental. Sometimes there’s a big mystery but it’s not as big as Oyeyemi’s question: Will the protagonist be okay inside herself?

Buy the Book

A Psalm for the Wild-Built

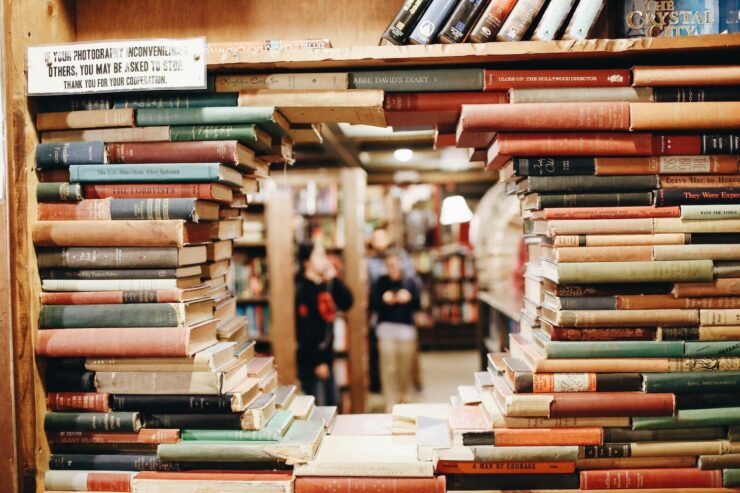

Where I run into trouble is when I want this question asked and answered in a fantasy setting. I want it in a world with magic and maybe dragons, with all the intense worldbuilding of epic fantasy; I want it taken fantasy-seriously. There are a lot of this kind of story to be found in the magical borderlands between fantasy and litfic, and I adore these books—the Oyeyemis, the Kelly Links, the Aimee Benders and Ruth Ozekis and Karen Russells; Quan Barry’s We Ride Upon Sticks and Madeline Miller’s Circe. I’ve found some in SF, too: Sarah Pinsker’s novels, Becky Chambers’ work, and Marissa Levien’s claustrophobic and terrifying The World Gives Way, among others. In SF, technology can provide the scale; the human crises can still be personal.

Does magic inherently raise the stakes? If we have magic, do we have to have conflict and power-based crises on a major scale? I know, technically, the answer is no. There is a whole small library’s worth of Patricia A. McKillip books that demonstrate that magic can exist and a book’s focus can still be low-key. Even Wicked, famous as it is, is about rewriting the Wicked Witch into her own story—not a figure out of nightmares but just a girl (albeit a green one) seen through the lens of a mythos she wants no part of.

But I want more.

I don’t like to call these small-stakes or low-stakes books, because the stakes of our own lives can feel anything but small or low. Maybe just personal-stakes books. Maybe they’re simply character-driven, though that can apply to so much. A friend recommended the thoroughly enjoyable The Ten Thousand Doors of January, which I liked a lot but felt had just slightly larger stakes than I wanted. A Twitter question on the topic offered up a lot of suggestions, many of which went onto a list of things to read soon. Others helped me narrow down some of my own personal criteria for books of this sort:

- No royalty or rulers of any kind as major characters;

- No chosen ones;

- No saving the world/kingdom/land/city.

What I want isn’t urban fantasy, though technically it often fits the bill, and isn’t light or comedic books, all of which are great in their ways but not what I mean by this specific kind of bookish desire. What I mean is a Kelly Link story grown to novel length. (Someday!) What I mean is Piranesi, in which the world is massive but it is home to only one lost man. What I mean is Karin Tidbeck’s The Memory Theater, which feels like the world and like one person’s dream at the same time.

I can think of these stories more in middle grade and YA spaces, perhaps because there’s an assumed coming-of-age aspect to many of those, and coming-of-age is about figuring out who you are and how you’ll be okay inside yourself. The first part of Lirael’s story, in Garth Nix’s novel, is entirely this: a girl trying to understand her place in a world that she doesn’t seem to fit into, adapting and growing and changing. Eventually she saves the world—twice! But that comes later. Destiny Soria’s Iron Cast and Michelle Ruiz Keil’s novels have this magical and intimate vibe, but take place in this world. But they inch closer to what I want.

Sometimes, well-known authors write these books and they get a little overlooked. Palimpsest is rarely the first Catherynne M. Valente book people mention, but it’s an absolute dream of intimacy, a magical sense of place, and bittersweet possibility. Robin Hobb is hardly unknown in fantasy circles, but her Liveship Traders series—books very concerned with the practicalities of life, with making a living and finding a place and surviving a difficult world—usually play second fiddle to the more epic-in-scope Fitz and Fool stories. (Though those novels, too, are grounded in the reality of her fantasy world, in the practical way Hobb uses work and status and power.)

But that’s what I want: fantasy books about people building their ordinary lives. Books about bookbinders and tavern-keepers, the people who raise horses and make boots, the troubled daughters setting out to find their own places in the world. (It often, for me, comes back to Tess of the Road.) You could maybe call it working-class fantasy, but that feels tied to capitalism in a way I don’t love. I want fantasy that breaks the rules of fantasy and lets the unheroic have their own life-sized adventures.

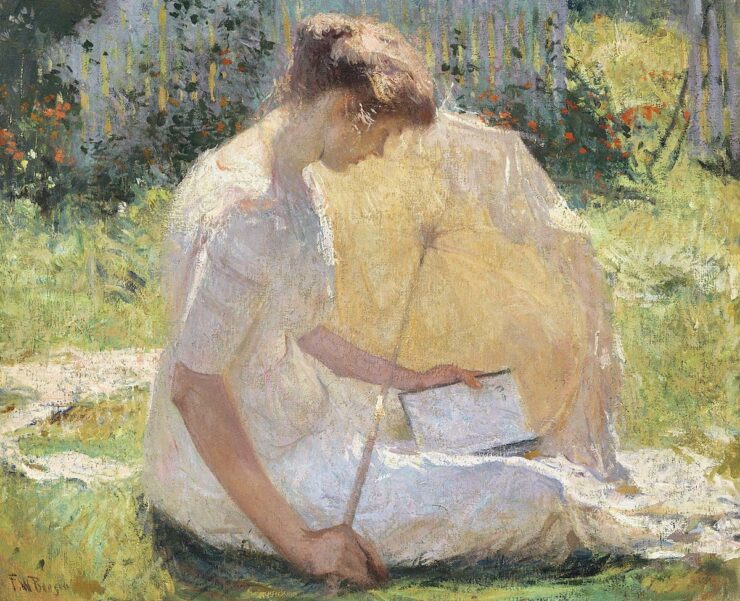

I try not to talk about Ursula K. Le Guin here too much, as I work part-time for her estate, and it can feel like tricky territory. But I have that job partly because I’m a lifelong Le Guin fan: A Wizard of Earthsea was the first fantasy novel I encountered, and that story looms large in how I read, and what I want from and look for in books. And it’s hard to think or write about reading and SFF without being influenced by Le Guin, who often asked still-relevant questions about science fiction, stories, and people, as she did in her 1976 essay “Science Fiction and Mrs. Brown.”

Le Guin starts with Virginia Woolf, who wrote about Mrs. Brown, a woman Woolf observed in a train carriage, a “clean, threadbare” old lady, with “something pinched about her.” Woolf watched the woman, eavesdropped on her, and noted how she looked “very frail and very heroic” when she disappeared into the station. “I believe that all novels begin with an old lady in the corner opposite,” Woolf wrote. “I believe that all novels, that is to say, deal with character.”

Le Guin takes this premise, accepts it, and then asks a question that still resonates, almost 40 years later: “Can the writer of science fiction sit down across from her?” Her question is, “Can a science fiction writer write a novel?” by Woolf’s definition, and also, “Is it advisable, is it desirable, that this should come to pass?” She answers both in the affirmative, and says a lot of very interesting things along the way about gender, and about We and Islandia and Frodo Baggins and some of her own work; she argues against her own position for a bit.

It’s a brilliant piece, and what I take from it—what I still look for in books—is encapsulated by the image of Mrs. Brown in a spaceship. In which books is there room for her, or her magical equivalent? Is this all I’m asking for: a book that sees the value, the heroism, in a threadbare woman on a train?

I will keep looking for Mrs. Brown. I’d love to know where you’ve found her.

Molly Templeton lives and writes in Oregon, and spends as much time as possible in the woods. Sometimes she talks about books on Twitter.